#alfonso XII

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alfonso XII

Artist: Federico De Madrazo y Kuntz (Spanish, 1815-1894)

Date: 1886

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain

Description

This is a posthumous portrait of the monarch. He appears standing, in full-length, and dressed in a simple captain-general's uniform, upon which he bears the grand laureate cross and sash of the military order of San Fernando (Saint Ferdinand), as well as the decorations of the Golden Fleece hanging from his collar and a cummerbund and a saber girdle around his waist. He poses inside a palatial hall, on a rich carpet, resting his hand on one of the splendid hard-stone tables kept in the Museo del Prado , on which we see the command baton and the feathered helmet of his uniform. In the shadows of the sumptuous architecture in the background, there is a niche with a statue of a medieval monarch – probably King Alfonso X the Wise, the immediate nominal predecessor of the monarch – and a medallion with the effigy of King Charles V.

Federico de Madrazo had already painted portraits of Alfonso XII on several occasions throughout the king's lifetime, according to the records in his inventory. However, this portrait was commissioned from the painter in 1886, the year following the king's death. It was intended for the Ministry of Public Works, which back then was home to the Contemporary Section of the Museo del Prado . It was immediately transferred to the Museum, probably with the purpose of being integrated within the Chronological Series of the Kings of Spain, a project initiated by José de Madrazo.

#portrait#oil on canvas#male#standing#full length#painting#spanish monarch#alfonso xii#captain uniform#military order of san fernando#palatial hall#hard stone table#statue#architecture#oil painting#posthumous#federico de madrazo y kuntz#spanish painter#spanish culture#spanish king#artwork#european art

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alleged last wishes of king Alfonso XII of Spain to his queen, Maria Christina of Austria-Tescgen, in his deathbed.

#“Keep your p*ssy at bay” said the man that didn’t keep in his pants for other women during their six years of marriage 😀#Alfonso XII#I hope this isn’t real but honestly I hardly wait anything good from this man#House of Bourbon#Wise counsel 🙃

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monumento de Alfonso XII en el Parque del Retiro en Madrid, ESPAÑA

#alfonso xii#monumento#monument#parque el retiro#el retiro park#madrid españa#madrid spain#europe#europa

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

last part

#bourbons#felipev#felipe v#louis i#louis of spain#isabel ii#alfonso xii#alfonso xiii#spain#carlos iii#carlos iv#fernando vi#fernando vii

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sería coherente abrir un burdel a los pies del monumento a Alfonso XII. (Y trasladar el centro de salud especializado en ETS, frecuentado por las trabajadoras sexuales, que hay en la calle Sandoval).

#fotografía#photography#original photographers#street photography#paisaje urbano#photographers on tumblr#fotos tumblr#madrid#julian callejo#alfonso XII#reyes#puteros

0 notes

Text

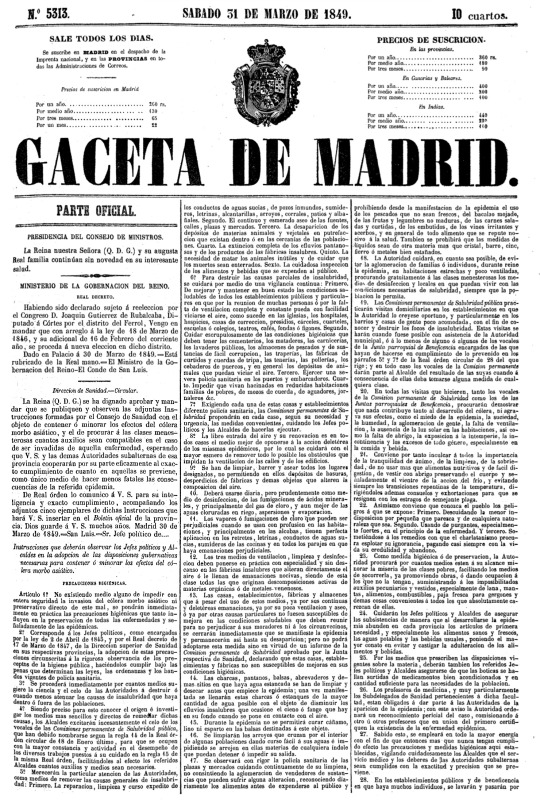

Pues aquí vamos.

La España del siglo XIX sufrió cinco epidemias de cólera morbo —aunque algunas fuentes solo consideran cuatro—, que abarcaron los siguientes años:

La primera, entre 1833-1834, que, a pesar del conocimiento que se tenía en el país del cólera y las medidas de contención aplicadas, logró penetrar en territorio nacional desde Portugal a Galicia y Andalucía. Al año siguiente afectaría a Castilla (ejem, ejem, guerras carlistas, ejem, ejem). Sería la de mayor número de muertos, con una cifra aproximada de 300.000 fallecidos; el doble que en los siguientes brotes,

La segunda, entre 1854-1856, que afectaría a las zonas del interior de la península, como Madrid.

La tercera, entre 1865-1866, se difundiría desde Valencia al resto del levante, aunque luego afectaría también a Barcelona, Zaragoza y Madrid. Contribuiría a una situación social que terminaría por desembocar en la Revolución Gloriosa, en 1868, con la expulsión de la reina Isabel II.

La cuarta, entre 1885-1886 (algunas fuentes marcan el origen del brote en 1884), sería una de las más virulentas, a pesar de que para ese momento se tenía gran conocimiento sobre el microorganismo que ocasionaba la enfermedad (Robert Koch había aislado al agente patógeno en 1883).

Y la quinta, entre 1890-1891, aunque, comparada con las anteriores, apenas fue significativa, junto a aquellas ocurridas a comienzos del siglo XX.

Debido a los graves efectos que tuvieron las tres última en la industria naciente del ferrocarril, he podido recuperar algunas de las instrucciones que se daban para intentar evitar la transmisión de la enfermedad en los últimos años.

Pocos antes del segundo brote, se publicaría la Real Orden e Instrucciones de Sanidad de 30 de marzo de 1849 en la Gaceta de Madrid, en la que se pueden destacar las medidas de limpieza, ventilación e higiene, el control sobre los alimentos de la policía sanitaria en los mercados y plazas, la fumigación con ácidos minerales y, principalmente gas de cloro —se habla del agua clorurada en riego, aspersiones y evaporación—, del procedimiento tras la muerte de un enfermo y de las instrucciones de las casas de socorro, hospitales y enfermerías coléricas, entre otras.

En un documento firmado por el Jefe del Servicio Sanitario de la Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte de España, Estaban Sánchez de Ocaña, con fecha de 13 de junio de 1885, se empieza explicando qué es la enfermedad del cólera-morbo-asiático, sus síntomas y las causas que lo provocan.

Entre estas, enumera la suciedad, la falta de ventilación, los excesos en las bebidas y comidas, la falta de limpieza en retretes, el uso de aguas contaminadas y la falta de precaución en el tratamiento y desinfección de las ropas y enseres de los coléricos.

A continuación, afirma que, con tal de garantizar un adecuado tratamiento y prevención del cólera, la única medida posible es garantizar el cumplimiento de los preceptos y consejos higiénicos dados en cuanto a las habitaciones, alimentos, bebidas, ropas y vestidos, limpieza personal y primeros auxilios y precauciones a adoptar con los enfermos.

A pesar de que no he podido acceder como tal al anterior, un documento de la Compañía de los Ferrocarriles de Madrid a Zaragoza y a Alicante, más concretamente en la Red Catalana, a fecha de 7 de septiembre de 1911, recoge la siguiente descripción:

*Bacillus virgula fue el nombre original del patógeno que le puso Koch, aunque se terminaría cambiando a Vibrio cholerae.

A continuación, pasaba a describir el modo de transmisión y métodos para su prevención, sobre todo a las personas que se dedicaban al cuidado del enfermo.

El mayor cuidado se debía tener con las fuentes de agua, que se debía hervir o filtrar de forma adecuada, y con los alimentos como ensaladas, verduras y frutas que no se pudiesen someter a la cocción.

Se partía del convencimiento —como se ha podido leer con anterioridad—, de que la temperatura de ebullición del agua, de 100º, era capaz de eliminar al patógeno por complejo.

Afortunadamente, en la actualidad se sabe que no producen esporas, una especie de forma de resistencia que algunas bacterias crean en condiciones desfavorables para que la colonia se vuelva a desarrollar en condiciones favorable, por lo que la esterilización era eficaz.

Posteriormente, daba detalles sobre cómo tratar el agua.

Se recomendaba, además, evitar las bebidas de extraña procedencia y las alcohólicas.

Aquellos con desarreglos digestivos se encontraban mucho más vulnerables a la infección, y, de hecho, en otro documento, publicado un año antes, en 1910, por la misma Compañía MZA, firmado por el director general R. Coderch y el doctor E. Varela, se detallaban las siguientes instrucciones, entres las que destacaba la de evitar las frutas verdes o pasadas.

Volviendo al documento del 7 de septiembre de 1911 que se estaba tratando anteriormente, añadía el consejo de evitar también los tomates y pimientos, incluso aunque estuviesen cocidos, y evitar el consumo de bebidas my frías.

También había que tener cuidado con la alimentación de los niños de corta edad, destacando aquellos en la dentición, debido a su predisposición a «desarreglos de vientre». Y evitar que el estómago y el vientre estuviesen expuestos al frío, especialmente después de las comidas.

El agua del mar, por supuesto, ni tocarla y más si estaba próxima a la desembocadura del alcantarillado, y había que tener especial cuidado si se decidía bañarse de no tragarla sin querer.

La limpieza de manos era esencial cuando se quería llevar cualquier cosa a la boca (incluso en la acción de liar un cigarrillo), y más cuando se había tenido en casa a un enfermo con cualquier síntoma intestinal, fuese o no cólera.

Continuaba con un párrafo en el que se describían los primeros síntomas del cólera, además de su evolución.

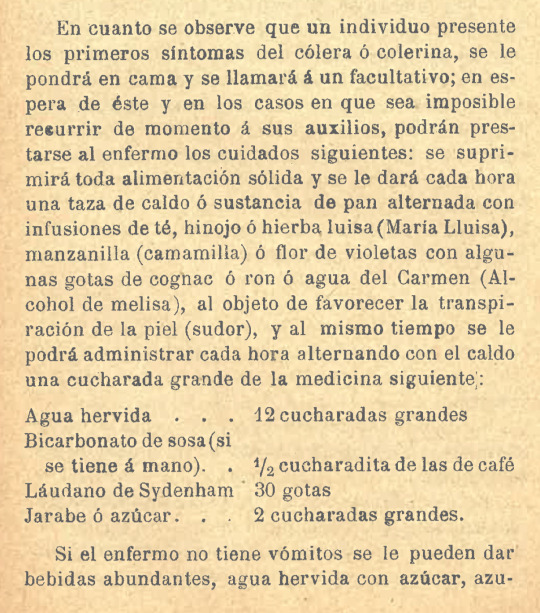

Para unos primeros auxilios antes de la llegada de un profesional, se adjuntaban las siguientes instrucciones.

El documento terminaba con las medidas de desinfección que se debían tomar en una casa en la que había un enfermo de cólera, remarcando la importancia de la limpieza y la ventilación.

También daba instrucciones sobre cómo realizar la fumigación, resaltando la importancia que tuvo esta estrategia en el cuarto brote de la enfermedad.

El suministro de medicamentos, sobre todo de los más urgentes, quedaba a disposición del Servicio Sanitario y los botiquines de todas las estaciones.

Estas instrucciones tan detalladas, como se ha podido ver, son muy posteriores a los cinco brotes del cólera, pero servirían para evitar epidemias tan severas como las que se habían vivido en el siglo anterior.

El cólera dejó muchas enseñanzas en cuanto salud pública y, también, algunas anécdotas, como es la visita de Alfonso XII a los enfermos del cólera en Aranjuez.

Y es que, el día 2 de julio de 1885, el Rey, que en esos momentos contaba con 27 años, salió sin avisar a nadie —salvo a su ayudante, que lo acompañaba—, hacia la estación de tren, desde donde viajaría a Aranjuez, arrasada por los efectos de la enfermedad. En la estación, por supuesto, lo reconocería el jefe de servicio, que le ofrecería viajar en un coche salón.

Alfonso lo rechazaría.

En Aranjuez, recorrería el hospital del Real Patrimonio y dos hospitales habilitados, uno en Casa de los Marinos y otro en un colegio. Repartió hasta 60.000 reales en limosnas, y todos los presentes pudieron ser testigos de cómo el monarca se aproximaba a las camas de los enfermos y les hablaba a modo de consuelo.

Incluso mantendría una conversación con un soldado natural de Murcia, lugar en el que el cólera también estaba presente —de hecho, se dice que el brote en Aranjuez se originó por un jornalero huido de Murcia—, en el que le diría que, si no había ido allí, era porque no había podido, pero que supiesen todos los españoles que él les acompañaba en sus aflicciones y en su desventura.

Al regresar el monarca a Atocha, todo el pueblo de Madrid sería testigo de una escena inédita; la reina, María Cristina, se tiró a abrazar al Rey recién bajado del tren, y ambos serían fumigados.

En todos los periódicos se leían titulares sobre que el Rey había desafiado al cólera. Sin embargo, ninguno sabía que Alfonso XII ya estaba enfermo de tuberculosis para aquellos momentos, su causa de fallecimiento el 25 de noviembre de ese mismo año, sin permitirle siquiera haber cumplido los 28.

Pero eso es otra historia.

En la actualidad, se sabe que el cólera es una enfermedad causada por el patógeno Vibrio cholerae, o, más concretamente, por la toxina que producen algunas de sus cepas.

A nivel molecular, esta toxina ocasiona la acción constante de un canal que expulsa iones cloruro de las células intestinales —el mismo canal cuyo defecto por causas genéticas desemboca en la fibrosis quística—, lo que produce también una salida de agua (básicamente, esta siempre se dirige a donde mayor concentración de iones haya para diluir) que termina por desembocar en una deshidratación extrema.

Como tratamiento, ahora se utilizan bebidas que incluyen en su composición agua, azúcar (glucosa) y sales minerales (sodio); estas dos últimas esenciales para la captación de agua en las células intestinales por mecanismos moleculares, además de antibióticos, que se especializan en atacar al patógeno y no a todas las células del huésped (como hacían los medicamentos de los que hablaban las guías a inicios del siglo XX).

Sin embargo, las infusiones, el agua hervida con azúcar y demás bebidas descritas en el documento adjuntado con anterioridad eran la principal clave para la lucha contra la enfermedad, puesto que rehidrataban el organismo del enfermo y evitaban el agravamiento de los síntomas y, por tanto, la muerte, para que el cuerpo pudiese, por sus propios medios, eliminar la toxina y sus efectos nocivos. De hecho, en 1911 ya se estaba hablando de «una vez pasada la enfermedad...».

Y ya está.

.

Glosario de enfermedades (detalles generales del cólera).

Hay una cierta parte de mi persona que me pide no dejar de lado las epidemias de cólera, y más en España.

Yo solo aviso.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Óbolo de Alfonso VII de León ''el Emperador'' con la leyenda ''Imperator Leoni''

#numismática#arqueología#reino de león#alfonso vii#península ibérica#españa#moneda#alfonso vii de león#monedas#edad media#siglo xii#coin#numismatics#archaeology#coins#kingdom of león#iberian peninsula#spain#middle ages#12th century#medieval period

1 note

·

View note

Text

#el ministerio del tiempo#emdt#emdt polls#francisco de sandoval y rojas#lope de vega#miguel de cervantes#charles howard#francisco martínez montiño#william shakespeare#antonio lópez y lópez#práxedes mateo sagasta#eusebi güell#alfonso xii de españa

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(vía Catedral de la Almudena, víspera de la Patrona de Madrid – FOTOGRARTE)

#Catedral#La Almudena#Catedrales Católicas#Catedrales Españolas#Madrid#siglo xix#Reina María de las Mercedes#Alfonso XII de España#Arquitectura#Arquitectura religiosa#Arte#Fotos nocturnas#Fotografías

0 notes

Text

Wprowadzenie

W ciągu dziejów fryzury męskie władców często odzwierciedlały ich władzę i status społeczny. Od wyszukanych peruk po skomplikowane warkocze, fryzury europejskich monarchów w XIV do XIX wieku nie były wyjątkiem. Fryzury te nie tylko były symbolem ich władzy, ale także sposobem na okazanie swojego bogactwa i statusu społecznego. Niektóre z najbardziej charakterystycznych fryzur z tego okresu to proszkowe peruki francuskiego dworu, płynące włosy z ery romantyzmu i schludne fryzury z przedziałkiem z epoki wiktoriańskiej. Przyjrzyjmy się bliżej fascynującym i często ekscentrycznym fryzurami europejskich władców od XIV do XIX wieku.

Einfluss religii i kultury na fryzury męskie

Fryzury męskie w Europie w XIV wieku były zdominowane przez wpływy religijne i kulturowe. Włosy były często układane w proste, mocno przyklejone kaski. W XIV wieku popularne było noszenie długich włosów, które były opuszczane na plecy lub związane w kucyk. Jednakże, w XVI wieku, fryzury męskie zaczęły zmieniać się pod wpływem renesansu i wzorów z antyku. Włosy były układane w skomplikowane upięcia, często z warkoczami, i często ozdabiane perłami lub innymi ozdobami.

W XVII wieku fryzury męskie stały się jeszcze bardziej skomplikowane i wyszukane, a peruki stały się powszechne. W XVIII wieku peruki zaczęły być coraz bardziej popularne, szczególnie we Francji i Anglii. Włosy były często pudrowane, aby uzyskać biały kolor, a peruki były często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami lub innymi ozdobami.

W XIX wieku fryzury męskie zaczęły się upraszczać, a peruki zaczęły wychodzić z mody. Mężczyźni zaczęli nosić włosy krótkie lub średniej długości, często z przedziałkiem pośrodku. Fryzury były schludne i proste, a włosy często były przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów.

Fryzury renesansowe

Włosy w epoce renesansu były układane w skomplikowane upięcia, często z warkoczami i ozdobami. Fryzury były inspirowane wzorami z antyku, a mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy. Peruki stały się również popularne w epoce renesansu, szczególnie wśród władców i arystokracji.

Włosy były często pudrowane, aby uzyskać biały kolor, a peruki były ozdabiane kokardami, perłami i innymi ozdobami. Fryzury renesansowe były bardzo skomplikowane i wymagały wielu godzin pracy, aby je ułożyć.

Włosy były często układane w kaski lub warkocze, a mężczyźni nosili również peruki. W XVIII wieku peruki stały się coraz bardziej skomplikowane, a pudrowanie włosów stało się popularne.

Fryzury epoki baroku

Fryzury męskie w epoce baroku były bardzo skomplikowane i ozdobione perukami i kwiatami. Włosy były często pudrowane, aby uzyskać biały kolor, i układane w skomplikowane upięcia. Fryzury były często bardzo ciężkie i wymagały specjalnych drutów, aby utrzymać je na głowie.

Włosy były często układane w kaski lub warkocze, a mężczyźni nosili również peruki. W XVIII wieku peruki stały się coraz bardziej skomplikowane, a pudrowanie włosów stało się popularne.

W epoce baroku mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy, często związane w kucyk. Peruki stały się również popularne, szczególnie wśród władców i arystokracji. Włosy były pudrowane i często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami i innymi ozdobami.

Fryzury epoki rokoka

Fryzury męskie w epoce rokoka były bardzo eleganckie i skomplikowane. Włosy były często pudrowane, aby uzyskać biały kolor, i układane w skomplikowane upięcia. Fryzury były ozdobione perłami, kwiatami i innymi ozdobami.

Włosy były często układane w kaski lub warkocze, a mężczyźni nosili również peruki. W XVIII wieku peruki stały się coraz bardziej skomplikowane, a pudrowanie włosów stało się popularne.

W epoce rokoka mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy, często związane w kucyk. Peruki stały się również popularne, szczególnie wśród władców i arystokracji. Włosy były pudrowane i często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami i innymi ozdobami.

Fryzury neoklasyczne z końca XVIII wieku

W epoce neoklasycznej mężczyźni zaczęli nosić proste, schludne fryzury. Włosy były często przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów, a przedziałek pośrodku był bardzo popularny. Peruki wychodziły z mody, a pudrowanie włosów stało się coraz rzadsze.

Fryzury męskie w epoce neoklasycznej były bardzo proste i schludne. Włosy były często przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów, a przedziałek pośrodku był bardzo popularny.

W epoce neoklasycznej mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy, często związane w kucyk. Peruki stały się również popularne, szczególnie wśród władców i arystokracji. Włosy były pudrowane i często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami i innymi ozdobami.

Fryzury romantyczne

W epoce romantycznej mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy. Fryzury były proste i naturalne, a peruki wychodziły z mody. Włosy były często przyciemniane, aby uzyskać bardziej naturalny kolor.

W epoce romantycznej mężczyźni zaczęli nosić długie, falujące włosy. Fryzury były proste i naturalne, a peruki wychodziły z mody. Włosy były często przyciemniane, aby uzyskać bardziej naturalny kolor.

Fryzury męskie w epoce romantycznej były bardzo proste i naturalne. Włosy były noszone długie i falujące, często związane w kucyk. Peruki wychodziły z mody, a warkocze były rzadziej używane.

Fryzury wiktoriańskie

W epoce wiktoriańskiej mężczyźni zaczęli nosić proste, schludne fryzury. Włosy były często przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów, a przedziałek pośrodku był bardzo popularny. Fryzury były bardzo eleganckie i schludne, a peruki wychodziły z mody.

Włosy były często noszone krótkie lub średniej długości, a przedziałek pośrodku był bardzo popularny. Fryzury były bardzo schludne i proste, a włosy często były przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów.

Wpływ polityczny i społeczny na fryzury męskie

Fryzury męskie w Europie w XIV do XIX wieku często były narzędziem politycznym i społecznym. Władców i arystokrację często zobowiązywano do noszenia określonych fryzur, aby okazać lojalność wobec króla lub rządu. Fryzury były również sposobem na okazanie swojego statusu społecznego i bogactwa.

W XVIII wieku peruki stały się bardzo popularne, szczególnie we Francji i Anglii. Włosy były często pudrowane, aby uzyskać biały kolor, a peruki były często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami lub innymi ozdobami.

W XIX wieku fryzury męskie zaczęły się upraszczać, a peruki zaczęły wychodzić z mody. Mężczyźni zaczęli nosić włosy krótkie lub średniej długości, często z przedziałkiem pośrodku. Fryzury były schludne i proste, a włosy często były przyklejane do głowy przy pomocy specjalnych preparatów.

Dziedzictwo fryzur męskich z XIV do XIX wieku

Fryzury męskie z XIV do XIX wieku pozostawiły wiele śladów w dzisiejszej modzie i kulturze. Niektóre fryzury, takie jak przedziałek pośrodku i proste, schludne fryzury, są wciąż popularne, szczególnie wśród mężczyzn. Mężczyźni nadal noszą długie włosy i warkocze, a peruki są używane w teatrze i filmie.

Fryzury męskie z XIV do XIX wieku były często skomplikowane i wymagały wielu godzin pracy, aby je ułożyć. Włosy były pudrowane i często ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami i innymi ozdobami. Fryzury te były nie tylko symbolem władzy i statusu społecznego, ale także wyrazem sztuki i kultury.

Podsumowanie

Fryzury męskie europejskich władców z XIV do XIX wieku były nie tylko symbolem władzy i statusu społecznego, ale także wyrazem sztuki i kultury. Włosy były pudrowane, układane w skomplikowane upięcia, a peruki były ozdabiane kwiatami, kokardami i innymi ozdobami. Fryzury te pozostawiły wiele śladów w dzisiejszej modzie i kulturze, i nadal inspirują projektantów i artystów na całym świecie.

#fryzura królów europejskich#KrólPrusCesarzNiemiecWilhelmIIHohenzollernfryzura#Leopoldzie II#królu Belgów fryzurą i brodą#Król Jan III Sobieski - jaką miał fryzurę#Konstytucja 3 Maja#Stanisław August Poniatowski i jego fryzura#Jaką fryzurę miał Władysław Jagiełło podczas bitwy pod Grunwaldem w 1410 roku#Louis Philippe I - Władcza Fryzura i Wybuch Rewolucji Lipcowej#Fryzura Króla Francji Ludwika XIV#Alfonso XII - Twórca pokoju i mężczyzna ze stylowymi bokobrodami

1 note

·

View note

Text

Happy 52nd birthday to Queen Letizia of Spain!

Born 15 September 1972, Letizia Ortiz Rocasolano is Queen of Spain as the wife of King Felipe VI.

Letizia was born in Oviedo, Asturias. She completed a bachelor's degree in journalism, at the Complutense University of Madrid, as well as a master's degree in audiovisual journalism at the Institute for Studies in Audiovisual Journalism. She worked as a journalist for ABC and EFE before becoming a news anchor at CNN+ and Televisión Española.

In August 2003, a few months before her engagement to Felipe, Prince of Asturias, Letizia was promoted to anchor of the TVE daily evening news programme Telediario 2, the most viewed newscast in Spain. In 2000, she reported from Washington, D.C., on the presidential elections. In September 2001, she broadcast live from Ground Zero following the 9/11 attacks in New York and in 2003, she filed reports from Iraq following the war.

On 1 November 2003, the Royal Household announced Letizia’s engagement to Prince Felipe. The wedding took place on 22 May 2004 in the Almudena Cathedral in Madrid. Letizia and Felipe have two daughters: Leonor, Princess of Asturias (18) and Infanta Sofía (17).

On 19 June 2014, Letizia became Queen of Spain with her husband's accession as Felipe VI. She is the first Spanish-born queen consort since Mercedes of Orléans, the first wife of Alfonso XII, in 1878. She is also the first Spanish queen to have been born as a commoner.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study of María Luisa of Parma (1-2), Private Cabinet of María Luisa of Parma (3), and Smoking Room of Alfonso XII (4-5), Royal Palace of Madrid #realessitios For more, follow @patrimnacional, the official account of Patrimonio Nacional, which manages Spain's royal sites | by kevinmu

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monumento a Alfonso XII. Parque Retiro, Madrid. Agosto ‘24🇪🇸

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The House of Borgia: End of a Dynasty (Part 4)

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | References |

While the Conclave elected Pope Pius III, Cesare was occupied trying to find allies. His old friend, King Louis XII, came to his aid, issuing a statement to Romagna that their Duke was "alive and well and the friend of the King of France". Not only Cesare had the French's support, but he also counted on Ferrara's troops to protect his claim on Romagna, as Lucrezia had persuaded her husband and father-in-law to fight in her brother's defence.

Once Romagna was relatively stable and Cesare felt better, he returned to Rome, where he met with Pius III and had his position as Captain confirmed. Not only that, but due to Cesare's clever theft of the Papal Treasury, Pius III was left financially dependent on him. By all accounts, Cesare's life would continue on exactly as it had under Rodrigo's papacy.

Unfortunately for Cesare, Pius III died twenty six days after being elected Pope. The next Pope, Julius II, had been an old enemy of Rodrigo, and upon his election, was swift to force the Borgias to surrender their lands in Romagna, even ordering the new Captain of the Papal Forces to arrest Cesare when he refused to comply.

After Cesare's arrest, Julius decided to put him on trial and encouraged those wronged by him to file claims for financial compensation. Not only that, but Julius also charged Cesare with the murder of two cardinals, whose deaths were believed to have been arranged by Rodrigo. These trials never occurred, as in April 1503, Cesare was released in exchange for his remaining territories in Romagna. Once free, he departed for Naples, which was under Spanish rule and where the rest of the Borgias had taken refuge, with the exception og Lucrezia, who remained with her husband in Ferrara. Hardly had Cesare set foot in Naples when he was imprisoned again, as King Ferdinand of Spain wished to hand Cesare back to Julius II in exchange for an alliance against the French.

Cesare would remain imprisoned in Spain until 1506, when he managed to escape prison and seek refuge with his brother-in-law, Juan d'Albret, King of Navarre. Taking advantage of a civil war wrecking through Navarre, Cesare offered his services as a military leader to help King Juan reclaim the kingdom. This would prove to be Cesare's downfall, as on 12 March 1507, he was killed in battle by the revolting troops.

Six weeks would pass until the news of his death reached Lucrazia, who was, by this point, the Duchess of Ferrara. It's said that upon learning of her brother's fate, she locked herself in her room and began to wail his name. In 1508, Lucrezia would finally give birth to a son by d'Este, named Ercole II, who would be followed by Ippolito in 1509, Leonora in 1515, Francesco in 1516 and Isabella Maria in 1519. This last birth proved itself to be terribly complicated and claimed the lives of both mother and daughter.

Rodrigo, due to being a pope, was given a tomb in the Basilica di San Pietro, near his uncle's resting place. In 1586, Rodrigo's bones were dug up and placed on a casket alongside Alfonso's, which, in 1610, was taken to Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli, where the casket was set aside and forgotten about until 1864, when it was unexpectedly found. It would take until 1889 for the joined remains to be once again given a proper tomb, with a stone memorial being carved in honour of Alfonso and Rodrigo.

Cesare was buried in a tomb by Juan d'Albret in the church of Santa Maria of Viana, in front of the high altar. His tomb, however, was destroyed by the bishop of Calahorra some time later, with Cesare's body being dumped in a hole outside the church. In 1945, the remains were exhumed and an autopsy was performed. The remains then bounced from place to place until finally being reburied in the church in 2007.

Lucrezia, meanwhile, was buried in Monastero del Corpus Domini, in Ferrara, alongside the other Dukes and Duchess of Ferrara. In time, Alfonso d'Este joined her, as did her children and grandchildren

Thus, the era of Borgia dominance came to a close. Although the family continued to hold titles in the subsequent years (most notably, Rodrigo's great-grandson, Francis Borgia, was canonized as a saint) they never reclaimed the formidable power they once commanded during Rodrigo's papacy. Yet, Rodrigo, Cesare, and Lucrezia did not fade into obscurity. Their legacy endured, capturing the public imagination for centuries to come. Indeed, as the chronicles of their lives spread through the courts of Europe, their reputation grew, blending reality and legend. Their lives continue to fascinate audiences, inspiring countless reinterpretations in literature, drama, and visual media even to this day.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Princesses at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. The average age at first marriage among these women was 16.

This list is composed of princesses of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707.

Eadgyth (Edith) of England, daughter of Edward the Elder: age 20 when she married Otto the Great, Holy Roman Emperor in 930 CE

Godgifu (Goda) of England, daughter of Æthelred the Unready: age 20 when she married Drogo of Mantes in 1024 CE

Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I: age 12 when she married Henry, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1114 CE

Marie I, Countess of Boulogne, daughter of Stephen of Blois: age 24 when she was abducted from her abbey by Matthew of Alsace and forced to marry him, in 1136 CE

Matilda of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married Henry the Lion in 1168 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry II: age 9 when she married Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170 CE

Joan of England, daughter of Henry II: age 12 when she married William II of Sicily in 1177 CE

Joan of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 11 when she married Alexander II of Scotland in 1221 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 21 when she married Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1235 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of John Lackland: age 9 when she married William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke in 1224 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Henry III: age 11 when she married Alexander III of Scotland in 1251 CE

Beatrice of England, daughter of Henry III: age 17 when she married John II, Duke of Brittany in 1260 CE

Eleanor of England, daughter of Edward I: age 24 when she married Henry III, Count of Bar in 1293 CE

Joan of Acre, daughter of Edward I: age 18 when she married Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester in 1290 CE

Margaret of England, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John II, Duke of Brabant in 1290 CE

Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, daughter of Edward I: age 15 when she married John I, Count of Holland in 1297 CE

Eleanor of Woodstock, daughter of Edward II: age 14 when she married Reginald II, Duke of Guelders in 1332 CE

Joan of the Tower, daughter of Edward II: age 7 when she married David II of Scotland in 1328 CE

Isabella of England, daughter of Edward III: age 33 when she married Enguerrand VII, Lord of Coucy in 1365 CE

Mary of Waltham, daughter of Edward III: age 16 when she married John IV, Duke of Brittany in 1361 CE

Margaret of Windsor, daughter of Edward III: age 13 when she married John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke in 1361 CE

Blanche of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 10 when she married Louis III, Elector Palatine in 1402 CE

Philippa of England, daughter of Henry IV: age 12 when she married Eric of Pomerania in 1406 CE

Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 20 when she married Henry VII in 1486 CE

Cecily of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married Ralph Scrope in 1485 CE

Anne of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 19 when she married Thomas Howard in 1494 CE

Catherine of York, daughter of Edward IV: age 16 when she married William Courtenay, Earl of Devon in 1495 CE

Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 14 when she married James IV of Scotland in 1503 CE

Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VII: age 18 when she married Louis XII of France in 1514 CE

Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII: age 38 when she married Philip II of Spain in 1554 CE

Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of James VI & I: age 17 when she married Frederick V, Elector Palatine in 1613 CE

Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 10 when she married William II, Prince of Orange in 1641 CE

Henrietta Stuart, daughter of Charles I: age 17 when she married Philippe II, Duke of Orleans in 1661 CE

Mary II of England, daughter of James II: age 15 when she married William III of Orange in 1677 CE

Anne, Queen of Great Britain, daughter of James II: age 18 when she married George of Denmark in 1683 CE

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

IMAGENES Y DATOS INTERESANTES DEL 26 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2024

Día de las Cajas, Año Internacional de los Camélidos.

San Esteban.

Tal día como hoy en el año 2006

Explota un oleoducto en Lagos (Nigeria), causando la muerte a más de 200 personas.

2004

Un potentísimo terremoto de nueve grados de magnitud desgarra el suelo marino de la isla indonesa de Sumatra, provocando olas de hasta 10 metros de altura que surcan el Océano Índico a grandes velocidades y se estrellan contra las costas sin aviso previo en comunidades marítimas de una docena de países. La magnitud del desastre es descomunal: al menos 230.000 personas pierden la vida y la onda de choque acorta el periodo de rotación del planeta unos tres microsegundos. (Hace 20 años)

1943

En el transcurso de la II Guerra Mundial, el Crucero de Batalla alemán Scharnhorst, al mando del Vicealmirante Bey, que tiene órdenes de interceptar al convoy aliado JW-55B que se dirige al puerto de Murmansk, en el Mar de Barents, se encuentra en este día con la fuerza de protección y escolta aliada, al mando del Vicealmirante Burnett, compuesta por los cruceros HMS Belfast, Duke of York, Jamaica y Norfolk. Tras una dura persecución y un duro combate con los navíos y aviones de la Royal Navy, el buque alemán resulta hundido sobreviviendo sólo 36 de sus 1.839 tripulantes. (Hace 81 años)

1908

Jack Johnson se convierte en el primer afro-americano en ganar el título Mundial de los pesos pesados de boxeo. (Hace 116 años)

1884

Mediante decreto, el Rey de España Alfonso XII proclama que ha "tomado el Río de Oro bajo su protección sobre la base de acuerdos concertados con los jefes de las tribus locales", al tiempo que el gobierno español comunica a todas las potencias extranjeras, según establece la Conferencia de Berlín y Acta del mismo nombre, tener bajo su protectorado los territorios de la costa existentes entre el cabo Bojador y el cabo Blanco, es decir, lo que habitualmente se llama Sahara Occidental. Expresada la conformidad, la ocupación quedará legalizada. Marruecos no opondrá ninguna objeción. (Hace 140 años)

1863

El nuevo invento de la electricidad llega a Europa con el encendido de los faros costeros del cabo de La Heve en Francia. (Hace 161 años)

1805

Francia y Austria ponen fin a la tercera guerra de coalición, mediante la firma de un tratado de paz en Presburgo (Eslovaquia), como fruto de la derrota sufrida por los austríacos ante Napoleón Bonaparte en la batalla de Austerlitz. El tratado es netamente favorable a los intereses franceses. Supondrá el final del Sacro Imperio Romano. (Hace 219 años)

1776

Durante la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos tiene lugar la Batalla de Trenton, una de las más importantes, cuando los soldados independentistas, al mando de George Washington, atraviesan el río Delaware de madrugada y caen rápidamente sobre la ciudad que da nombre a la Batalla, cogiendo casi completamente desprevenidas a las tropas de Hesse (mercenarios alemanes contratados por los británicos). Los mercenarios oponen resistencia inicialmente, pero cuando se les corta la retirada, se rinden. Los independentistas regresarán a Pennsylvania con un millar de prisioneros y grandes cantidades de armamento y provisiones. Esta victoria dará nuevos bríos a las tropas de Washington, que conseguirán otro importante triunfo en la batalla de Princeton el 3 de enero de 1777, provocando finalmente la retirada de los británicos de los territorios de Nueva Jersey. (Hace 248 años)

2 notes

·

View notes